| The Beijen/Beyen Family Site by Laurens Beijen |

|

|

The homepage The overview of the site The next page The previous page |

The list of first names The photo gallery Searching this website Comments or questions |

Born in 1889Dirk Jan Beijen (G 13.32), was born in 1889 in Bussum. He was the first child of his eponymous father and his wife Jansje Hamming.After the main character of this page, six more children followed, three of whom died at a young age. The family moved from Bussum to Amsterdam in 1890, where they lived at various addresses, including in the part of the municipality of Nieuwer-Amstel that would be added to Amsterdam in 1896. After 1900 the father left his family and went to live in Hilversum. The divorce was not granted until 1922. Jansje Hamming stayed in Amsterdam with the children. Little is known about Dirk Jan's youth. According to the register of conscripts, he was a warehouse clerk in 1908. In 1909 he entered military service in the field artillery. Married to Martha GemertIn 1914 Dirk Jan Beijen married Martha Geertruida Gemert in Vledder in Drenthe. She was born in Amsterdam in 1890, but her widowed mother lived in Vledder. Dirk Jan lived still in Amsterdam. In the marriage certificate he was referred to as a forwarding agent.Dirk Jan and Martha had two children, both of whom were born in Amsterdam: Martha Geertruida in 1916 and Dirk Johannes (not the usual Dirk Jan this time) in 1919.  Above a photo of Dirk Jan Beijen and his wife Martha Beijen Gemert, below a photo of Dirk Jan and Martha with their children Martha and Dick. The photos were taken around 1930.  Maison de BonneterieIn 1916 and 1919, Dirk Jan Beijen was referred to as a warehouse clerk in the birth certificates of his children. When he witnessed his mother's second wedding in 1923, he was called a shop manager. He was probably already working at the fashion department store Maison de Bonneterie in Amsterdam.The Bonneterie was an extremely luxurious store owned by the Jewish Cohen family. The business started in 1889 on the Kalverstraat and was expanded in 1909 with a new, much larger wing on the Rokin. Hundreds of staff were employed. Below a photo of the shop on the Rokin in 1912.  Dirk Jan Beijen rose to become chief buyer and caretaker at the Bonneterie. He and his family lived next to the department store in the house 150 Rokin. Beijen was one of the few non-Jewish executives in the company. The anti-Jewish measures after the German occupation in 1940 had major consequences for the Bonneterie. In 1941, the director Alfred Cohen was forced to leave the business and the store came under German management. All Jewish employees were fired. In exchange for handing over a valuable collection of paintings to the Germans, Alfred Cohen and a number of family members were given safe conduct to Spain in January 1942, from where they later left for America via Portugal. Dirk Jan Beijen succeeded in preserving as much of the Bonneterie as possible and returning the shop to the rightful owners after the war. Mrs. Ellen Herz 'David, one of the Bonneterie's post-war directors, told me in a telephone conversation in 1997 that the owners were very grateful to him for that.

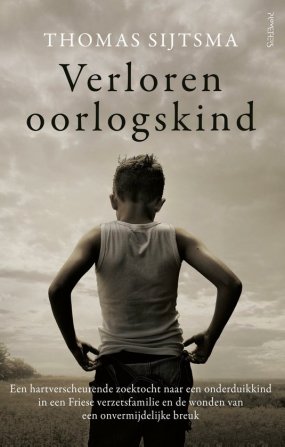

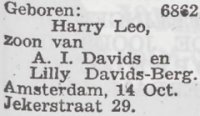

'Verloren oorlogskind' (Lost war child)Dirk Jan Beijen plays an important role in the book Verloren oorlogskind by Thomas Sijtsma, which was published in May 2022. I was able to make a modest contribution to that book. Inge Vecht-Prenzlau, who often came to the Bonneterie with her mother before the war, told Thomas Sijtsma about caretaker Beijen: "All clothing entered the store through him. He saw everything. I found him strict, even a little angry. Some people were afraid of him. I saw that as a child. He waved the scepter in the old-fashioned way. When Beijen was at work and he came in, everyone immediately stood in line. You knew immediately what to do with him. The man was straightforward and consistent." During the war, Inge Prenzlau spent some time in hiding with her parents in Dirk Jan Beijen's house. Then she also got to know other sides of him. The main character of Verloren oorlogskind is Harry Davids, a Jewish boy who was born in October 1942 in Amsterdam. His parents were the young couple Alfred Davids and Lilly Davids Berg. Despite the dangerous times, they placed a birth announcement in a Jewish weekly newspaper that was then still published in Amsterdam.  Alfred Davids had worked at the Bonneterie until he was fired by the new administrators. Alfred and Lilly therefore knew Dirk Jan Beijen well, and they also came to his house on the Rokin.

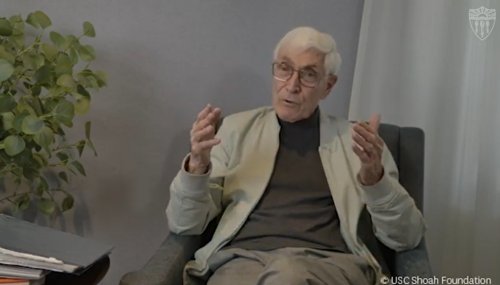

After Harry was born, they changed their mind. Beijen and others managed to convince them that it was impossible to go into hiding with a baby: that would be irrevocably noticed. With great difficulty they agreed that Harry should be taken away by a girl who had contacts with an organization looking for families to house Jewish babies. For security reasons, they were not allowed to know the girl's name and where Harry was going. Dirk Jan Beijen knew that: Harry was placed with the family of the metalworker Gerard den Os in the Javastraat in Amsterdam. Beijen made sure that the family received money every month for the maintenance of the child. Thomas Sijtsma wrote in the book: "In any case, Dirk Jan Beijen was invaluable in hiding Harry. His name cannot be mentioned often enough. He turned up several times in official documents, although after the war he rarely if ever flirted with his help to employees of Maison de Bonneterie. Beijen brought a sum of money to Den Os once a month to provide for Harry's living. For me that was proof that Beijen was very closely involved with the Davids family. (...) The caretaker of Maison de Bonneterie, who so sternly and fervently addressed subordinate colleagues, turned out to have a grandiose heart. He rejected no one when help was requested. After the war, stories came out of Jews who had been helped by him. He must have had to work on it a lot, the stress was enormous." After Alfred and Lilly had to let go of their child, they stayed for a while in Dirk Jan Beijen's house on the Rokin. When the chance of a raid there became too great, he looked for another place for them. Thomas Sijtsma discovered that it must have been in the hold of a Rhine barge. There they were most likely betrayed. Alfred and Lilly Davids Berg were murdered in April 1943 in the Sobibor extermination camp. After a few months, Harry's hiding place was also betrayed. Den Os, his wife, his daughter and a young Jewish woman in hiding were taken away by the Germans. Harry was left in the house for the time being because there was no room for him in the robbery van. Before the Germans returned, resistance fighters managed to take the baby with them. Not long after, a young woman took the child to Friesland on the Amsterdam-Lemmer ferry. Harry stayed there in succession at a number of hiding addresses, until he was finally taken in by the family of the post office owner Berend Bakker and his wife Jeltje in Engwierum, east of Dokkum. After the war, Harry Davids was assigned to an uncle who lived in South Africa, much to the chagrin of his hiding family. He later moved to America. Thomas Sijtsma, a great-grandson of Berend and Jeltje Bakker, managed to make contact with him. At the presentation of the book in May 2022, Harry Davids, then 79 years old, was also present. After the warDirk Jan Beijen came out of the war as a widower. He has said little about the important work he did during the occupation years. His family didn't know much about it either.In September 1945 he remarried the then 36-year-old Pieta van Scheers. Below is a photo of them in their later years.  After the liberation, Beijen played an important role in rebuilding the plundered Bonneterie. In 1958 he received a medal of honor in silver, associated with the Order of Orange-Nassau. Dirk Jan Beijen died in 1973, his widow Pieta Beijen van Scheers in 1985. A message from Harry DavidsIn the afterword to Verloren oorlogskind, Harry Davids wrote that since his retirement, he has considered it his personal life's goal to tell others about the fate of his family, and about the Bakker family and the others who saved his life. He regularly gives lectures at schools and museums in Los Angeles. Below is a still from a video from 2024, when he was 81. On October 18, 2025, I received a message from the now 83-year-old Harry Davids via the contact form on this website: By chance, I found your Family site, which includes reference to how your ancestor Dirk Jan Beijen/Beyen had helped with the hiding of my parents, Alfred and Lilly Davids, during the German occupation. My father worked at de Bonneterie, which was owned by his uncle Alfred Cohen together with "Tante" Rosa Cohen-Wittgenstein, who was related to my mother. My mother's great-uncle Sally Berg was the co-owner of Hirsch et Cie. My mother and her brother worked at Hirsch, whilst my father was working at de Bonneterie, until the germans "aryanized" Jewish owned businesses. After my parents married in 1941, Alfred Cohen allowed them to live in his second home, located on Jan van Goyenkade 2 in Amsterdam. They signed a Huurcontract which is in my possession. Later, the Germans seized the property and my parents were forced to move to de Rivierenbuurt, where I was born in 1942. It was from that address that I was taken to the Den Os family in de Javastraat for hiding. I believe that was arranged by Dirk Beijen. He also sent money to the Den Os family to help pay for me during my onderdak there. So I am thankful to your ancestor for being an "upstander" in keeping me alive. When I am asked to speak about my survival at schools and museums I include his name as an "upstander." Harry Davids assumed I was a descendant of Dirk Jan Beijen. I've explained to him that I'm a very very distant cousin of Dirk Jan. It is striking that he used several Dutch words in his message, such as Tante (Aunt), Huurcontract (Rental agreement) and onderdak (shelter). |

|

The next page The homepage The overview of the site |

The top of the page Searching this website Comments or questions |